May 4, 2018 at 12:16AM

via www.wired.co.uk

The companies that provide our email, online shopping and family photo-sharing accounts are also in the business of training, managing and communicating with weapons of war.

Firms that started out as search engines and book retailers have become dominant forces in online service provision and artificial intelligence, for which national governments and military agencies are an obvious client base.

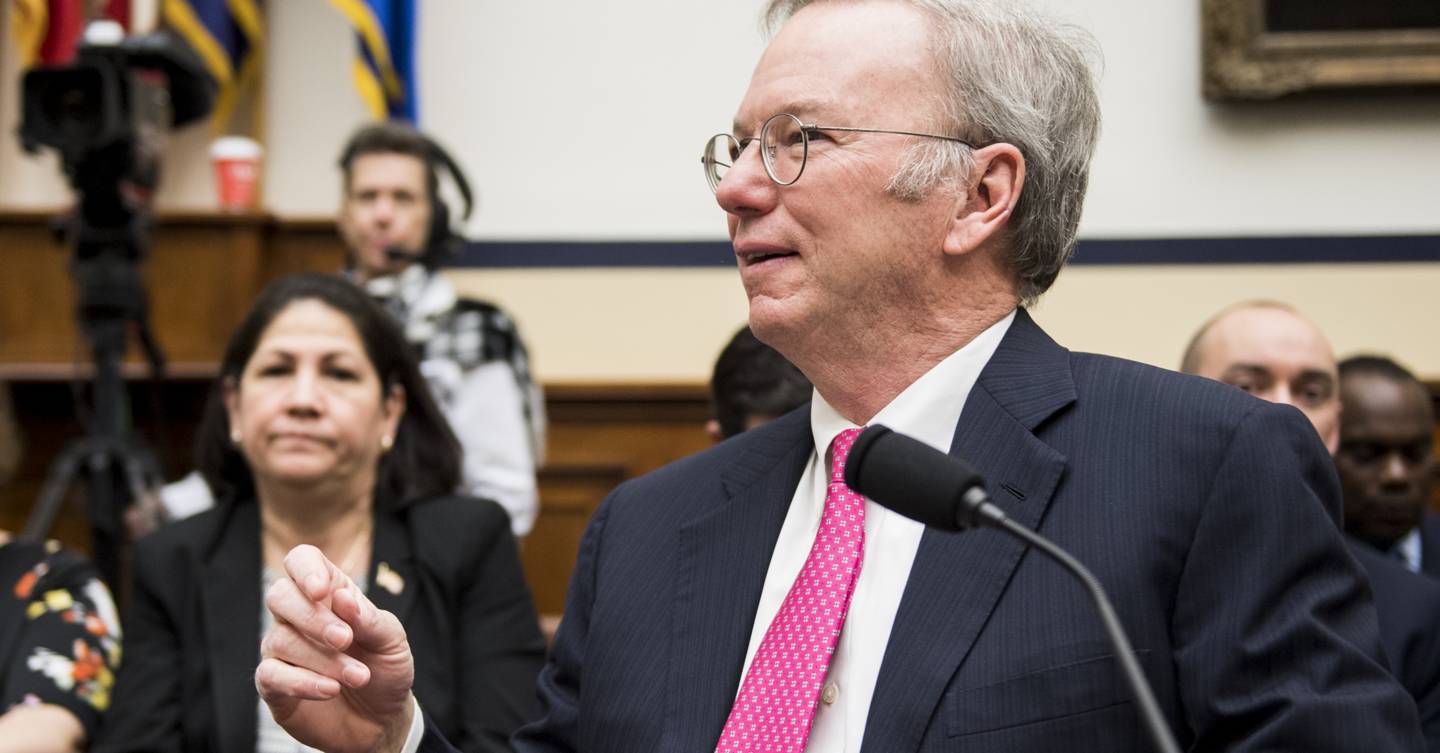

Just ask Eric Schmidt, Alphabet board member and former Google executive chairman, who is also an advisor to the US Department of Defense. Last month, he addressed the House Armed Services Committee, commenting that "any military that fails to pursue enterprise‑wide cloud computing isn’t serious about winning future conflicts."

Google's involvement in the development of Project Maven, a drone vision system created in collaboration with the US military's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) has proved so controversial that it prompted over 3,000 Google employees to write a letter to CEO Sundar Pichai, asking for the project to be cancelled and "that Google draft, publicise and enforce a clear policy stating that neither Google nor its contractors will ever build warfare technology".

Google says that its work on Project Maven is "specifically scoped to be for non-offensive purposes ... to flag images for human review and is intended to save lives and save people from having to do highly tedious work". But military contracts can be an uncomfortable fit with the life-affirming, internationalist corporate culture professed by many of Silicon Valley's biggest firms, despite the well-established relationship between the US military and private technology sectors.

This raises an important question: is it still possible to disentangle consumer technology firms from warfare? And if we can't, are there viable alternatives for conscientious consumers?

US Air Force

Mary Wareham, coordinator of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots – part of Human Rights Watch – wrote to Google last month recommending "that Google adopt a proactive public policy committing not to engage in work aimed at the development and acquisition of fully autonomous weapons systems".

She received "a swift and friendly response that did not answer our questions", but the charity is continuing to engage with Google "in a dialogue with Google to encourage the company to take a firm stand against fully autonomous weapons and in support of preemptively banning them".

How did we get from 'don't be evil' to drone warfare?

Google's already shaky "don't be evil" motto wasn't extended to Alphabet when it was spun up as Google's new parent company in 2015. As business gets bigger, evil becomes harder to avoid. Alphabet's undertaking to "do the right thing" is similarly not exactly what most people would associated with business activities that include training military drone vision systems.

As this latest generation of tech firms has discovered, military contracts are a tried and tested path towards corporate growth and technological development. The US is the best example of an economic model that uses military funding to fuel research in the fields of science and technology.

This economic stimulation takes several forms:

- Research carried out by the military, such as Darpa's development of GPS and the internet

- Military research grants to universities and other institutions, such as the Digital Library Initiative project that funded Sergey Brin and Larry Page's early work on automated web crawling at Stanford University

- Military contracts like SpaceX and United Launch Alliance's contracts to launch US government spy satellites

Other economic models for driving technological development exist, such as the kind of direct civilian government funding used by Japan, the European Union and Cuba, but many of the world's biggest tech companies are economically bound up in the fortunes of the military sector.

Amazon

"Those who have made their money and foundations via the business and military applications of this technology do tend to think that the only way forward is through that continued intersection, partially due to the fact that this is what's driven so much of the tech industry, thus far," says PhD researcher Damien Williams of Virginia Tech's Department of Science, Technology, and Society. "But thinking about AI in this way has the potential for massively dangerous consequences."

Williams, a specialist in the ethics and philosophy of nonhuman consciousness, argues that such systems need to be built differently to avoid a a corporate race for the best threat analysis and response algorithms which is likely to become a "zero-sum game" where only one side wins. "This is not a perspective suited to devise, for instance, a thriving flourishing life for everything on this planet, or a minimisation of violence and warfare," he adds.

Jennifer Gibson, head of human rights charity Reprieve’s drones project, says that the problem is the intent to kill, as much as the technology involved in the killing: "what Google is doing as part of Project Maven is moving the US ever closer to machine killing. The US drone programme under human control has already led to the deaths of thousands, including many innocent men, women and children. Killing by algorithm can’t fix the bad intelligence feeding the targeting."

What can consumers do?

While it's relatively easy to get a (somewhat) ethical pension, getting ethical online services, for those who'd rather not count the armed forces among their fellow customers, can be more of a challenge.

It's impossible to separate this history of internet from that of military research, built as it is on technology from the US military's ARPANET in the 1970s. However, the modern internet's infrastructure is now in the hands of private ISPs and telecommunications carriers.

Smaller companies are less likely to have military contracts and can provide better features, too, as in the case of secure email provider Protonmail and Mega, which provides 50GB of encrypted, zero-knowledge storage.

Open source software is another valuable resource for those seeking both more ethical computing and those who'd like more control over their PCs. Because open source software is effectively held in the commons – available to everyone to use and modify as they choose – the economic and profit factors of proprietary software and services don't apply in the same way.

This makes operating systems such as the Ubuntu Mate or Slackware Linux distributions and cross-platform desktop tools like GIMP and LibreOffice, a more comfortable ethical fit for some people who'd prefer not to give their money to companies actively engaged in war work.

But this is where things get more complicated. Various governments and armed forces organisations have developed their own versions of Linux, while some major open source service providers such as Red Hat work directly with national military organisations.

For the more technical, a hosted server, such as those provided by Vultr with open source tools like OwnCloud for online file sharing and Rainloop webmail can provide an effective alternative to large-scale commercial cloud services, with the added bonus of sharing less of your private data with advertising companies.

But simply leaving a service won't have any impact if the company doesn't know why you've left. If you're taking your custom away from Google or Microsoft because you don't like the fact that they work with the military, tell them this when you leave.

Individual customers are worth less to these corporate behemoths than huge government clients, but for those who are strongly opposed to the role of mainstream tech firms in the arms industry, it's an opportunity to be part of a larger movement, as well as taking a personal ethical stand.

Is it time for a revolution in ethical tech?

The utopian promise of technology is that of a future that contains less death, war and misery than our past. In providing tools for use in war, tech's most ubiquitous firms are defying that promise and, in many cases, their own principled foundations.

But there are few campaigns or petitions against military involvement by the companies that control our online lives. That's understandable – while it's easy to demonstrate against an arms fair, the companies that provide our online services can seem as inescapable as utility firms.

Banks and many of FTSE 500 firms that you'll find in pension and investment plans are just as enmeshed in the global arms trade and military development, as illustrated by The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons's recent Don't Bank on the Bomb campaign. In response, ethical investments are growing in popularity.

While military contracts have been part of the tech sector for as long as it's existed, they don't have to be part of its future. To create a better, less militaristic future for tech, we need to keep asking inconvenient questions of the companies we do businesses with.

Here's how the big three currently stack up...

Report card: Alphabet

Alphabet has only relatively recently moved into the defence sector and, of all the firms we've looked at it, it may have the most uncomfortable cultural fit with the industry, despite the enthusiasm of senior figures such as Eric Schmidt.

When Google bought robotics firm Boston Dynamics – subsequently sold to SoftBank – in 2014, Google said that it would not accept further funding from Darpa.

Project Maven was first publicised in July 2017, although the scope of Google's involvement wasn't made clear at the time.

Later the same year, Eric Schmidt dicussed his role on the US military's Defense Innovation Board. "There’s a general concern in the tech community of somehow the military-industrial complex using their stuff to kill people incorrectly," he said at the time. But he also predicted that, over time, there will be tech companies founded "that are more in alignment with the mission and values of the military".

Google received certification required to compete for US government contracts in March 2018 and is one of a number of firms competing for the $10 billion Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) military services contract.

In April 2018, Schmidt told the US government's House Armed Services Committee that "if DoD is to become 'AI‑ready', it must continue down the pathway that Project Maven paved and create a foundation for similar projects to flourish, in addition to its basic research efforts".

When contacted for this article, a Google spokesperson said the company "won't have anything new to add beyond what has already been widely covered and discussed" in the New York Times and BBC.

Report card: Amazon

Amazon, one of the world's largest providers of cloud services, has ensured that its AWS data centres meet security requirements for government projects, including those in the defence sector, with particular focus on US military and intelligence contracts.

AWS provides Cloud Computing for Defense services and Amazon says that "Cloud technology is the latest development in the defense world providing for expansion in warfighter potency. It has the capability to transform the warfighter all while keeping data and highly classified information safe and secure." Yes, the same Amazon that you buy books from.

With the launch of its AWS Secret Region, Amazon has been certified for work across all US national security systems, including those that require a level 6 SECRET classification. "We are the only Cloud Service Provider accredited to address the full range of DoD data classifications, including Unclassified, Sensitive, Secret, and Top Secret," AWS boasts.

While many of these projects are, in the nature of defence contracts, rarely publicised, Amazon is specifically marketing its Rekognition machine vision system at the defence sector. The company even developed an Alexa skill that can alert DoD personnel when its cloud-based recognition system using Rekognition identifies an individual on a watch list in an image.

Report card: Microsoft

Microsoft has a long history of defence sector work, which in the UK, includes Windows for Warships, commissioned by the Royal Navy. It also provides dedicated cloud services to the MoD in a private Office 365 instance

The Microsoft Azure Government Cloud platform is rated for SECRET classified work in the US, with services including Blockchain for Azure Government, "cognitive capabilities, artificial intelligence, and predictive analytics."

Microsoft did not have a spokesperson available to comment for this story.